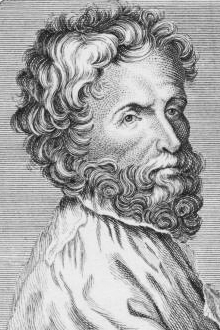

Cristóbal de Morales

Cristóbal de Morales may have been the most famous composer of sacred music in all western Europe in the period between the death of Josquin in 1521 and the rise of Palestrina and Lassus in the 1550s. But at the same time, he remains a mysterious and tragic figure in the history of Renaissance music.

Morales was born in Seville around 1500 or a little before, and if he was educated in the cathedral school there, as seems most likely, he certainly had talented teachers: Pedro de Escobar was master of the choirboys at Seville from 1507 to 1513/14, and Francisco de Peñalosa, who was officially employed by the royal chapel, spent a good deal of his time in Seville and considered the city his home. In 1534, after chapelmaster jobs in Ávila and Plasencia, Morales joined the papal choir in Rome, and during the eleven years he spent either there or on travels with the Pope’s retinue he found lasting international success, appearing in printed anthologies (but with his name prominent in their titles) as early as 1540, and publishing two large books of Masses under his own name in 1544. But by the time he left Rome to become chapelmaster at Toledo Cathedral in 1545, something had gone very wrong.

Morales’s absences seem to have begun early in his time at the Vatican, and, as the years went on, they became more frequent and longer, and were more carefully specified as being the result of illness. The exact nature of his ailment is never explained; recurrent malaria has been suggested, as well as rheumatoid arthritis, and here in the twenty-first century it is easy to wonder about, say, bipolar disorder. For whatever its effects on Morales’s life as a singer, the illness did not seem to slow down his productivity as a composer. Even in the Toledo period, when he was plagued with further illness, serious financial problems, musical dissatisfactions and difficulties in managing the choirboys under his care, he remained at the top of his artistic game, as revealed in the glorious service music recently recovered by Michael Noone from the water-damaged manuscript Toledo 25.

In any case, Morales lasted less than two years in Toledo before resigning in August 1547 and moving on to lowlier employment—and continued illness and unhappiness—in Marchena and Málaga. In the summer of 1552 the chapelmastership at Toledo came open again; Morales applied and, in a move that suggests that he was not remembered warmly, was required to compete for the position with the other candidates. But before the competition could be held, he died, somewhere in his early fifties.

It’s a sad story of frustration, disappointment and misery, told in short prosaic documents that individually conceal much but accumulate their melancholy weight as Morales’s life goes on. And it is a story made all the more poignant by the beauty of the music he has left behind which, at its best—and it is often at its best—combines the elegance and the imitative virtuosity of the so-called post-Josquin generation (the ‘perfected style’ in Richard Taruskin’s perceptive words) with a clarity and a human intensity not often seen in his Northern contemporaries.